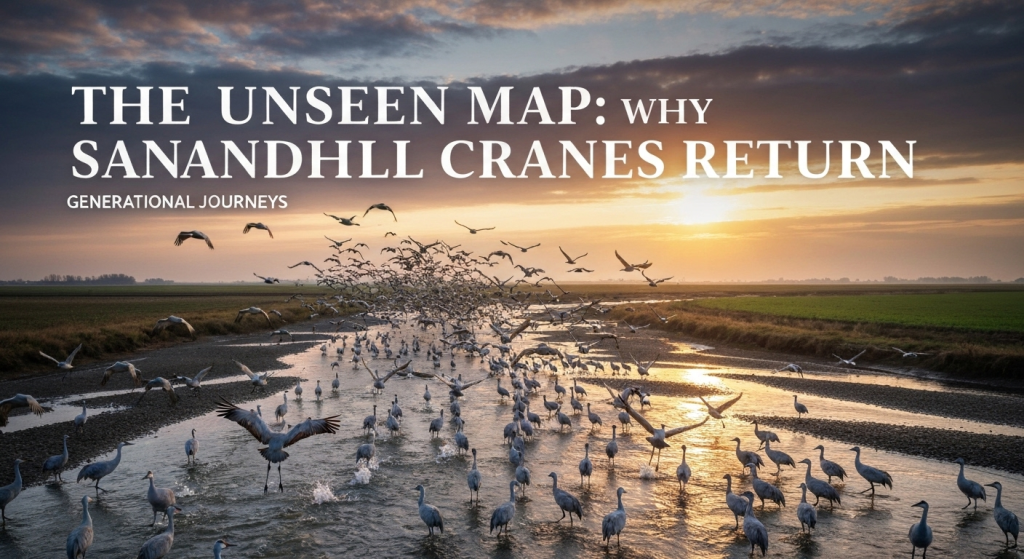

Every spring, a spectacle of ancient proportions unfolds in the skies and fields across North America. The air fills with a rattling, primordial call as immense flocks of Sandhill Cranes descend upon specific, seemingly ordinary fields. It’s not a random landing. They return to these exact locations with pinpoint accuracy, year after year, generation after generation. This incredible phenomenon isn’t just a quirk of nature; it’s a complex behavior driven by memory, tradition, and a deep, instinctual understanding of the land. It’s a behavior known as site fidelity, and it’s the key to understanding one of the world’s most breathtaking migrations.

My name is Mahnoor Farooq, and for years, I’ve been captivated by the lives of birds. My work involves more than just identifying species; it’s about understanding the “why” behind their behaviors. The unwavering loyalty of Sandhill Cranes to their migratory stopover points has always been a source of wonder for me. Spending time in places like Nebraska’s Platte River Valley, I’ve seen firsthand how these birds are not just passing through but are deeply connected to the landscape. This article is a culmination of that field experience and research, breaking down the science and tradition that guide these magnificent birds back to the same patch of earth every single year.

Understanding Site Fidelity: The Crane’s Unbreakable Bond with Place

At its core, the reason Sandhill Cranes return to the same fields is a survival strategy called site fidelity. Think of it as an animal’s loyalty to a previously occupied location. For cranes, this isn’t just a sentimental attachment; it’s a life-saving calculation. Returning to a known location means they are guaranteed to find the resources they need to survive their grueling migration. They know the food is there, they know where to find safe shelter for the night, and they don’t have to waste precious energy searching for a new, unproven spot.

This behavior provides a massive evolutionary advantage. By sticking to tried-and-true locations, cranes increase their chances of survival and, consequently, their reproductive success. A well-fed, well-rested crane is a healthy crane, better equipped to complete its journey to the breeding grounds and raise the next generation. From my own observations, the predictability is stunning. You can almost set your calendar by their arrival in certain regions, a testament to how deeply ingrained this behavior is.

More Than Just Memory: Is it Instinct or Intelligence?

So, what’s driving this remarkable navigational feat? Is it pure instinct, a kind of pre-programmed GPS, or is it a learned skill? The answer is a fascinating mix of both. Cranes are born with an innate urge to migrate, a biological trigger that tells them when it’s time to move. However, the specific route—the “unseen map” they follow—is not something they’re born knowing. It’s a learned tradition.

This blend of instinct and learning is what makes their migration so robust and successful. The instinct provides the push, while the learned knowledge provides the precise directions. Let’s break down how these two components work together.

| Behavioral Driver | Role in Migration | Description |

| Instinct (Innate) | The “Why” and “When” | A genetic, hardwired impulse to migrate south for the winter and north for the summer. This is triggered by changes in day length and weather patterns. |

| Learning (Acquired) | The “Where” and “How” | The specific route, including critical feeding fields and safe roosting spots, is learned by young cranes from their parents and other experienced adults in the flock. |

This dual system ensures that even if a crane gets separated from its family, the basic instinct to migrate remains. However, the most successful individuals are those who have learned the specific, resource-rich waypoints that have sustained their ancestors for centuries.

The Generational GPS: How Cranes Pass Down Ancient Routes

The most critical part of this entire process is the transfer of knowledge from one generation to the next. Sandhill Cranes are excellent parents, and their teaching extends far beyond basic survival skills. Young cranes, known as “colts,” stick close to their parents for their first 9 to 10 months. This period includes their very first full migration journey—south in the fall and north again in the spring.

During this inaugural trip, the colts are essentially students. They fly alongside their parents, memorizing every landmark, every river bend, and every crucial stopover field. They learn which agricultural fields offer the best waste grains, which wetlands are safest from predators, and how to use wind currents to conserve energy. It’s a year-long apprenticeship in the sky. Observing a family group is a powerful experience; you can see the constant communication and the way the young birds mirror the adults’ movements. It’s a silent lesson in survival passed through the air.

This social learning is reinforced by the flock. Cranes migrate in large family groups and social flocks, meaning a young bird isn’t just learning from its parents but from a whole community of experienced travelers. This collective memory ensures the integrity of the route is maintained, even if one family group is lost.

What Makes a Field Perfect? The Habitat Checklist for a Crane Stopover

Sandhill Cranes are incredibly particular about their stopover sites. Not just any field or river will do. For a location to become a traditional staging area, it must meet a strict set of criteria that cater to their three most important needs: food, safety, and open space.

The Perfect Dining Spot: Food and Foraging Needs

Migration is an energy-intensive process. Cranes must consume enough calories to fuel thousands of miles of flight. Their diet during this time is rich in carbohydrates and fats, providing the necessary fuel.

- Waste Grains: Modern agriculture has become an accidental ally to the cranes. After the harvest, fields of corn, wheat, and sorghum are littered with leftover grains. Cranes have learned to exploit this abundant and easily accessible food source. They spend their days methodically walking through these fields, gleaning the waste grain.

- Natural Foods: While grains are a staple, they also supplement their diet with natural foods found in nearby wet meadows and pastures. They use their strong beaks to dig for tubers, seeds, insects, snails, and even small vertebrates like mice and frogs.

- Proximity is Key: An ideal staging area has these rich feeding grounds located within a few miles of their nightly roosting sites. This minimizes the energy they have to spend flying between their “bedroom” and their “kitchen.”

Safe Harbor: Roosting on the River

After a long day of feeding, cranes need a safe place to rest. Their choice of lodging is very specific and designed entirely around predator avoidance. They roost standing up in the wide, shallow channels of braided rivers.

The Platte River in Nebraska is the quintessential example. Its waters are typically only a few inches deep, and its channels are often hundreds of feet wide, dotted with sandbars. This unique geography provides a perfect defense system.

- Natural Alarm: Predators like coyotes or bobcats cannot sneak up on the flock without splashing in the water. This sound immediately alerts the thousands of roosting cranes, giving them ample time to take flight.

- Clear Sightlines: The wide-open nature of the river means there is no vegetation for predators to hide behind.

From my time on the Platte, the evening return to the roost is the most magical part of the day. The sky darkens as wave after wave of cranes descend, their calls echoing across the valley, until the river is a shimmering, noisy carpet of birds settling in for the night.

An Unobstructed View: The Need for Open Spaces

Whether they are feeding or roosting, Sandhill Cranes rely on their excellent eyesight to detect danger from afar. This is why they exclusively use wide-open habitats. They avoid forests or areas with dense, tall vegetation because these landscapes limit their field of view and could conceal a lurking predator. Agricultural fields, prairies, and broad river valleys provide the unobstructed, 360-degree view they need to feel secure.

The Platte River: A Case Study in Crane Loyalty

To truly appreciate the power of site fidelity, one only needs to look at the Platte River Valley in central Nebraska. This 75-mile stretch of river is the single most important stopover location for Sandhill Cranes in the world. It is the bottleneck for the entire mid-continent population.

Each spring, an estimated 600,000 Sandhill Cranes—more than 80% of the world’s population—converge here for a few weeks to rest and refuel before continuing their journey north to their breeding grounds in Canada, Alaska, and even Siberia.

| Platte River Feature | Why It Attracts Cranes |

| Wide, Braided Channels | Provides extremely safe roosting sites with shallow water and sandbars, preventing surprise attacks from land-based predators. |

| Adjacent Farmland | Surrounding fields of corn and soybeans offer a massive and reliable source of high-energy waste grain to fatten up for the next leg of migration. |

| Historical Precedent | This has been a critical migratory route for millennia. The knowledge of this “oasis” is deeply embedded in the cranes’ collective, learned memory. |

| Central Location | It is perfectly positioned geographically along their migratory flyway, serving as a natural halfway point for rest and recovery. |

The Daily Rhythm on the Platte

Life for a crane on the Platte follows a strict daily schedule. Just before sunrise, the river comes alive with a cacophony of calls. In small groups, they lift off and head out to the surrounding cornfields to spend the day feeding, socializing, and performing their spectacular dancing rituals. As dusk approaches, the process reverses. Flock after flock streams back to the river, circling gracefully before settling onto their chosen sandbar for the night. This rhythm is the heartbeat of the Great Plains in March.

Threats to Tradition: Challenges Facing Crane Migration Routes

While the Sandhill Crane migration is a story of resilience, it is not without its challenges. The very traditions that have ensured their survival are now being threatened by a rapidly changing world.

- Habitat Loss: The most significant threat is the alteration of their critical stopover habitats. Dam construction and water diversion for agriculture have reduced the flow of rivers like the Platte, allowing vegetation to encroach on the open channels and sandbars that cranes need for safe roosting. Urban sprawl also consumes the farmland they rely on for food.

- Agricultural Changes: Modern farming is becoming more efficient. While this is good for farmers, it means less waste grain is left in the fields after harvest, potentially reducing the food supply for cranes.

- Climate Change: A warming climate can create a mismatch between the timing of migration and the availability of food sources. If spring arrives earlier in the north, cranes may not have enough time at their stopover sites to build the energy reserves they need for successful breeding.

Conservation efforts are underway to protect these vital corridors. Organizations are working to manage water flows, preserve habitats, and partner with farmers to ensure that the ancient traditions of the Sandhill Crane can continue for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

How far do Sandhill Cranes migrate?

Sandhill Cranes can travel thousands of miles. Some populations that winter in Texas or Mexico will fly all the way to breeding grounds in the high Arctic of Alaska and Siberia, a one-way trip that can exceed 3,000 miles.

Do all Sandhill Cranes migrate?

No. While most populations are migratory, there are a few non-migratory (or “sedentary”) populations that live year-round in milder climates, such as in Florida and Cuba. These cranes do not need to migrate because they have access to adequate food and safe habitats throughout the year.

How long do young cranes stay with their parents?

A young crane, or colt, stays with its parents for about 9 to 10 months. It learns the complete migration route by following them south in the fall and back north in the spring before becoming independent.

Why do cranes make that rattling sound?

The loud, rattling, bugle-like call of the Sandhill Crane is one of the most distinctive sounds in nature. It is produced by a very long trachea (windpipe) that coils within their sternum, acting like a brass instrument. This unique call, which can be heard from over a mile away, is used for communication within the flock.

Conclusion: An Ancient Journey Continues

The annual return of the Sandhill Cranes is far more than a simple flight from one point to another. It is a breathtaking display of instinct, intelligence, and deeply rooted tradition. Their unwavering loyalty to specific fields and rivers—their site fidelity—is a testament to a survival strategy perfected over millions of years. This behavior, passed down from parent to child, connects modern cranes to their ancient ancestors and to the very fabric of the landscape. By understanding the intricate needs behind this journey, we can better appreciate and protect the habitats that ensure this timeless, beautiful spectacle continues to grace our skies.