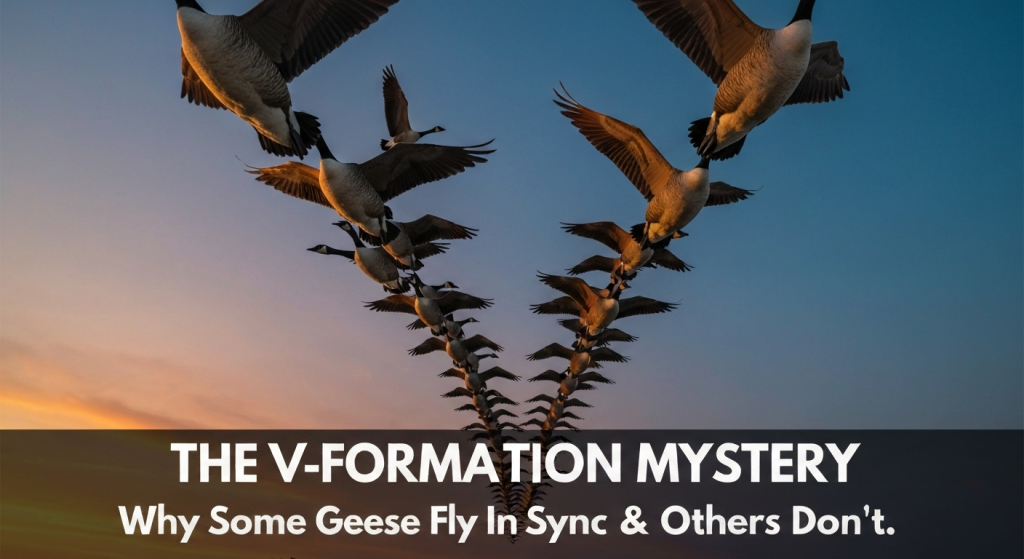

Have you ever looked up on a crisp autumn day and seen it? That perfect, moving arrowhead in the sky—a flock of geese, honking as they power their way south. It’s a sight so familiar it feels like a natural part of the changing seasons. We see it and instinctively know that a long journey is underway. But it also sparks a simple question: why that specific V-shape? And if it’s such a great idea, why don’t all birds do it? Even more puzzling, why do we sometimes see geese flying in a messy, disorganized group?

The truth is, the V-formation is a masterpiece of natural engineering, a brilliant solution to the immense challenge of long-distance migration. It’s all about physics, teamwork, and survival. But it’s not a one-size-fits-all strategy. The decision to form up or fly loose comes down to the specific needs of the flight, from the distance they need to cover to the number of birds in the group. This article breaks down the science behind this incredible behavior, exploring when the V-formation is essential and when it’s simply not worth the effort.

My name is Mahnoor Farooq, and for years, I’ve been fascinated by the incredible behaviors of birds. My work involves spending countless hours in the field, observing, and then diving into the research to connect what I see with the science behind it. I don’t just read the studies; I try to understand the why—the evolutionary pressures that shape these complex strategies. My goal has always been to translate dense scientific findings into clear, relatable stories for fellow nature enthusiasts. Sharing the genius behind something as elegant as a V-formation is what drives my passion for the avian world.

The Science of the V: More Than Just a Pretty Pattern

At its core, the V-formation is a clever trick to make flying easier. It’s not about aesthetics or following a leader in a symbolic way; it’s a direct application of aerodynamic principles to conserve precious energy. When a bird flies, its wings create a difference in air pressure that generates lift. A side effect of this is that the air rolling off the wingtips forms a swirling vortex, known as a vortex wake. This wake has two parts: a downward-moving current directly behind the wingtip (downwash) and an upward-moving current just outside of it (upwash).

Here’s the thing: flying into downwash is like trying to run uphill—it forces a bird to work harder to stay airborne. But flying in the upwash is like getting a free boost. It’s like a cyclist drafting behind a competitor to reduce wind resistance. By positioning themselves correctly, the geese following the leader can ride on this wave of rising air, letting the bird in front do some of the heavy lifting.

This isn’t just a theory; it has been proven with remarkable precision. Research has shown that birds flying in a V-formation can reduce their energy expenditure significantly. One landmark study on pelicans found that their heart rates were much lower when flying in formation compared to when flying solo. The energy savings are estimated to be as high as 71% for birds in the optimal positions. That’s a massive advantage when you have to fly for thousands of miles.

| Flying Style | Energy Expenditure | Heart Rate | Effective Range |

| Solo Flight | High | Significantly Elevated | Limited by Individual Stamina |

| V-Formation Flight | Low to Moderate | Reduced by 15-30% | Extended by up to 71% |

This energy saving is the single most important reason why migratory birds adopt the V-formation. It allows the entire flock to travel farther, arrive at their destination in better condition, and increase their overall chances of survival.

Sharing the Burden: Why the Leader Isn’t Always the Leader

Flying at the point of the V is the most physically demanding position. This lead bird has no one in front to break the air and receives no aerodynamic advantage from the flock. It is cutting through undisturbed air, creating the upwash that benefits everyone else. If one bird were to stay in this position for the entire migratory journey, it would become exhausted long before the rest of the flock.

To solve this problem, geese and other formation-flying birds use a strategy of rotating leadership. It’s a beautiful and highly effective example of cooperation. After a period of time, the lead bird will drop back into one of the trailing positions in the V to recover. A different bird from the flock then moves up to take its place at the front.

From my own observations in the field, this transition is incredibly fluid. You can watch a flock through binoculars and see the lead bird peel away from the point, seamlessly sliding into a spot further down the line while another bird moves forward to take on the tough job. There’s no chaos, no break in the formation’s rhythm. This cooperative behavior ensures that the burden of leadership is shared equally among the strong flyers in the group.

The Benefits of Teamwork

This system of rotation offers several key advantages:

- Maximizes Flock Endurance: By sharing the most difficult role, the flock ensures that no single bird becomes overly fatigued, allowing the entire group to fly for longer periods.

- Promotes Fairness: The system is inherently fair, preventing the exploitation of any one individual for the benefit of the group.

- Utilizes Collective Strength: It allows the flock to leverage the combined strength of all its members, making the collective much more resilient than any single bird.

This isn’t just instinct; it’s a learned social dynamic that is crucial for the success of their epic journeys. The constant honking you hear is part of this—it’s communication, often interpreted as birds encouraging the leader and keeping the flock in sync.

The V-Formation Club: Who Flies This Way and Why?

The V-formation isn’t a universal flight strategy in the bird world. It is almost exclusively used by larger birds that undertake long, arduous migrations. You’ll commonly see it in species like:

- Geese (especially Canada Geese and Snow Geese)

- Pelicans

- Cormorants

- Ibises

- Cranes

The common thread here is body size and flight style. These are heavy birds with a steady, powerful wingbeat. For them, every bit of energy saved makes a huge difference over hundreds or thousands of miles. The aerodynamic benefits are substantial enough to justify the coordination required to maintain the formation.

Why Smaller Birds Don’t Bother

You will never see a flock of sparrows, finches, or warblers flying in a V-formation. There are a few reasons for this. First, their flight style is completely different. Small songbirds have a more erratic, bounding flight pattern—a series of rapid wing beats followed by a short glide. This flitting motion doesn’t create the stable, predictable vortex wakes needed for effective formation flying.

Second, for a small bird, the energy savings would be minimal and not worth the effort of precise positioning. Instead, small birds often fly in loose, swirling swarms or clouds. This type of flocking, often called a murmuration in starlings, serves a different purpose: predator avoidance. A dense, unpredictable swarm of thousands of tiny birds makes it incredibly difficult for a hawk or falcon to single out and attack an individual. Their safety is in numbers and chaos, not in aerodynamic efficiency.

| Feature | V-Formation Flocks | Swarming Flocks |

| Primary Purpose | Energy Conservation | Predator Avoidance |

| Bird Size | Large (Geese, Pelicans) | Small (Starlings, Sparrows) |

| Flight Style | Steady, Rhythmic Wingbeats | Erratic, Flitting Movements |

| Structure | Organized, Geometric Shape | Disorganized, Fluid Cloud |

| Key Benefit | Increased Flight Range | Safety in Numbers |

Context is Key: When the V-Formation Makes Sense

This brings us to the other half of the mystery: why do we sometimes see geese, the poster children for V-formations, flying in a disorganized gaggle? The answer is that the V-formation is a tool for a specific job: long-distance, high-altitude flight. When the job changes, so does the strategy.

Altitude and Distance Matter

Geese engage the V-formation primarily during their seasonal migrations. During these journeys, they fly at high altitudes where the air is thinner and there are fewer obstacles. The formation provides stability and efficiency that is critical for crossing vast distances.

However, not every flight is a marathon. Throughout the day, geese make many short trips. They might fly from a lake where they roosted overnight to a nearby cornfield to feed. This could be a flight of just a few hundred yards or a couple of miles. For these short-distance flights, the energy savings from forming a perfect V are negligible. The effort required to get organized and maintain precise spacing simply isn’t worth it. On these short trips, you’re far more likely to see them flying in a loose group, a simple line, or a chaotic jumble.

Flock Size and Formation

The effectiveness of a V-formation also depends on having enough birds to create it. A small family group of three or four geese won’t be able to form a proper V that provides significant aerodynamic benefits. They may fly in a simple line or just stay close together. A large flock of 20 or more birds, however, has the numbers needed to create a stable and efficient V, often with two long arms trailing the leader.

The use of the V-formation can be summarized with a simple pros-and-cons list.

Pros:

- Major Energy Savings: Allows for much longer flight distances.

- Clear Communication: Every bird can see the others, aiding coordination.

- Simple Navigation: The entire flock can easily follow the experienced leaders.

Cons:

- Requires Coordination: Takes effort to maintain proper spacing.

- Not for Short Flights: The energy benefits are irrelevant for short trips.

- Needs Enough Birds: Ineffective for very small groups.

So, the next time you see a disorganized flock of geese, they’re probably not lost or confused. They’re likely just making a quick, local trip where efficiency takes a backseat to convenience.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do geese honk so much when they fly?

Honking is their primary method of in-flight communication. Geese honk to coordinate their positions within the formation, to signal changes in speed or direction, and many researchers believe they honk to encourage the lead bird and each other during the strenuous flight.

Do V-formations always have sides of equal length?

No, very often they don’t. The shape of the V can be asymmetrical and can change dynamically based on wind conditions, the number of birds, and which birds are taking their turn to rest in the easier positions.

Do geese have one permanent leader for the entire journey?

Absolutely not. The lead position is far too tiring to be held by a single bird. Geese rotate the leader position regularly, allowing different birds to take on the difficult work while others recover in the formation’s wake.

What happens if a goose gets sick or injured and has to leave the formation?

According to observations from hunters and bird watchers, if a goose falls out of formation, it is often accompanied by one or two other geese who will stay with it until it either recovers or dies. This demonstrates the strong social bonds within the flock.

Conclusion

The goose’s V-formation is one of nature’s most elegant and visible examples of sophisticated cooperation. It’s a strategy born from the immense physical demands of migration, allowing these remarkable birds to travel thousands of miles by sharing the workload and harnessing the laws of physics. It’s a perfect blend of efficiency, teamwork, and communication.

But it is also a specialized tool. The choice to fly in a V or a loose gaggle is a practical one, dictated by the length and purpose of the journey. Understanding this helps us see that geese aren’t just blindly following an instinct; they are adapting their behavior to the needs of the moment. So the next time you see that arrowhead in the sky, you’ll know you’re not just watching a flock of birds, but a highly efficient, cooperative team on an incredible journey. And if you see them flying in a messy group over a local field, you’ll know they’re just taking a well-deserved short trip, saving their energy for the long road ahead.