The image of a flamingo is unmistakable. A flock of these vibrant, long-legged birds standing in shimmering blue water is one of nature’s most iconic sights. Their brilliant pink and reddish hues seem almost artificial, like something painted by an artist with a flair for the dramatic. This has led to one of the most common questions I hear from fellow bird enthusiasts: are they born that way? The simple answer is no, and the real story is a fascinating lesson in biology that perfectly illustrates the old saying, “you are what you eat.” The secret to their famous color isn’t in their DNA, but in their dinner.

My fascination with bird life began years ago, and the flamingo has always held a special place in my studies. For author Mahnoor Farooq, exploring and writing about Bird Species has been a journey of constant discovery. Spending years observing these creatures, both in literature and through binoculars, has deepened my appreciation for the intricate links between an animal, its environment, and its diet. My goal isn’t to be a formal academic but to share the “why” behind what we see in a way that feels clear and exciting. The flamingo’s coloration is a perfect example of nature’s hidden chemistry, and breaking it down reveals a story of adaptation, health, and survival.

The Secret Ingredient: Unpacking Carotenoids

The entire process behind a flamingo’s color begins with a specific type of organic pigment called a carotenoid. You’ve encountered these pigments your whole life, even if you didn’t know their name. They are the natural compounds that give many plants their bright colors. The orange of a carrot, the red of a ripe tomato, and the yellow of autumn leaves are all thanks to carotenoids. Birds, including flamingos, cannot produce these pigments on their own. To get them, they have to eat them.

Here’s the thing: the flamingo isn’t just eating one thing to get its color. It’s consuming a whole menu of organisms that are packed with these color-giving compounds.

What Exactly Are Carotenoids?

Let’s break it down a bit further. Carotenoids are a class of over 750 naturally occurring pigments synthesized by plants, algae, and photosynthetic bacteria. When an animal eats these plants or bacteria, the pigments are stored in their fat and can then be expressed in their skin, scales, or feathers.

For flamingos, the two most important carotenoids are Canthaxanthin and Astaxanthin. These are responsible for the deep pink and reddish colors we associate with the most vibrant flamingos. Think of them as super-concentrated dyes. While beta-carotene (found in carrots) gives a more orange-yellow hue, the compounds in the flamingo’s diet deliver that signature rosy pink.

The Flamingo’s Grocery List: Where They Find These Pigments

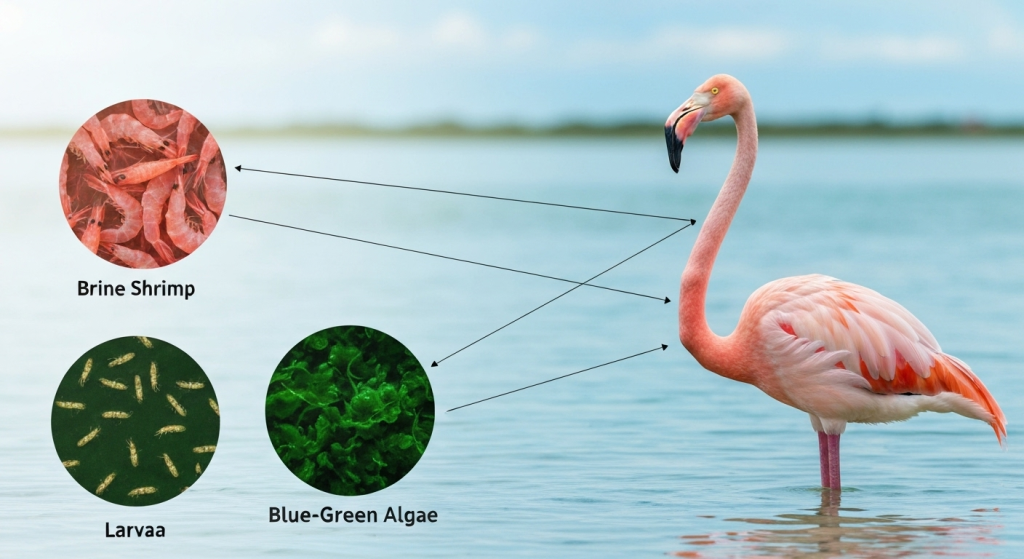

Flamingos are filter-feeders, using their specialized beaks upside down to strain food from the water in lagoons, salt pans, and estuaries. Their diet is the crucial delivery system for carotenoids. The primary sources include:

- Blue-green algae (Spirulina): This is the foundation. This algae is a powerhouse of carotenoid production.

- Brine Shrimp: These tiny crustaceans feast on the algae, concentrating the pigments in their own bodies.

- Larvae and Small Insects: Similar to brine shrimp, these critters also consume algae.

- Mollusks and Crustaceans: These are also key parts of the diet that contribute to the pigment load.

Essentially, flamingos are at the top of a short, colorful food chain. The algae make the pigment, the shrimp and larvae eat the algae, and the flamingos eat the shrimp and larvae. The more carotenoid-rich food a flamingo eats, the more intensely colored it becomes.

| Flamingo Species | Primary Diet | Typical Habitat | Resulting Color Intensity |

| American Flamingo | Brine shrimp, insect larvae, mollusks | Caribbean, Yucatán Peninsula | Bright pink to reddish-orange |

| Lesser Flamingo | Blue-green algae (Spirulina) | Sub-Saharan Africa, India | Paler, more delicate pink |

| Greater Flamingo | Brine shrimp, insects, mollusks | Africa, Southern Europe, Asia | The palest species, often whitish-pink |

| Andean Flamingo | Diatoms (a type of algae) | Andes mountains in South America | Pale pink body, yellow legs |

This table shows how a species’ specific diet directly impacts its coloration. It’s not a one-size-fits-all pink.

From Meal to Plumage: The Metabolic Journey

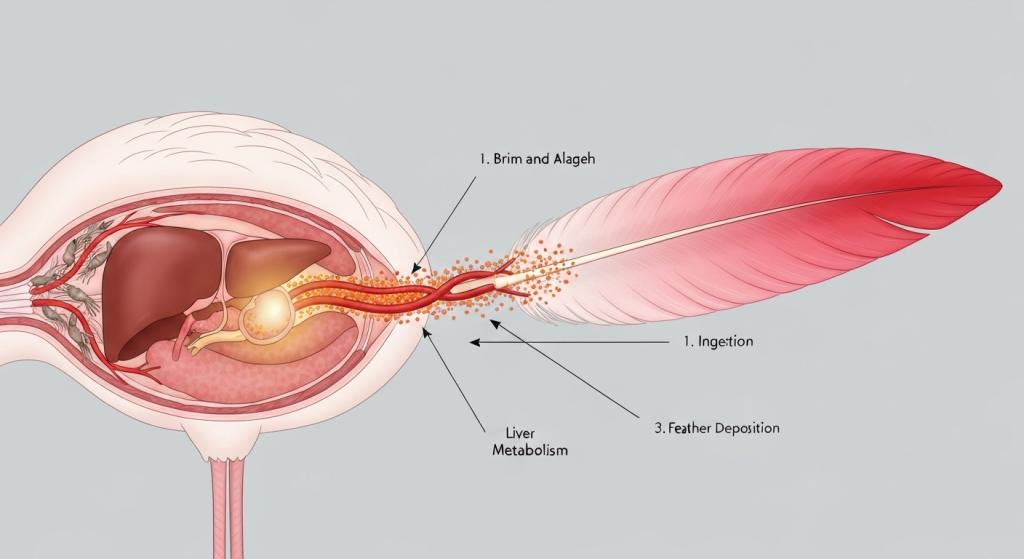

Eating carotenoid-rich food is just the first step. The real magic happens inside the flamingo’s body, where a complex metabolic process turns a simple meal into a stunning set of feathers. This biological pathway is a masterpiece of efficiency, ensuring that not a drop of color goes to waste. It’s a journey that starts in the digestive system and ends in the very structure of each feather.

The Digestive Breakdown

Once a flamingo swallows a mouthful of brine shrimp and algae, its digestive system gets to work. Enzymes in the liver play the lead role here. They break down the carotenoids from the food source and modify them into specific pigment molecules that the flamingo can use.

This is a critical step. The flamingo isn’t just passively absorbing the color. Its body is actively converting the raw pigments into the final, usable form. This metabolic process is unique to flamingos and a few other bird species, which is why you don’t see pink sparrows or pigeons. The liver processes these pigments and attaches them to fat molecules, which can then be transported through the bloodstream to various parts of the body.

Pigment Deposition: Painting the Feathers Pink

As new feathers grow, the fat molecules carrying the carotenoid pigments are deposited into the keratin that forms the feather structure. The pigments are literally locked into the feather as it develops. This is why a flamingo’s color is so uniform and deep. It’s not just a surface coating; it’s integrated into the very fiber of the feather.

This process also explains why molting is so important. When a flamingo loses its old, faded feathers, the new ones that grow in are infused with a fresh supply of pigment from its recent diet. From my years working in and observing bird conservation efforts, it’s always striking to see the difference in a flamingo’s vibrancy before and after a molt, especially if their diet has been particularly rich. The color also gets deposited in other areas, like the skin on their legs and face and even their beak, giving them an all-over rosy glow.

A Spectrum of Pink: Why Not All Flamingos Look the Same

If you’ve ever seen different groups of flamingos, you may have noticed that their shades of pink can vary dramatically. Some are a pale, almost white-pink, while others are a startlingly deep crimson. This variation isn’t random. It’s a direct reflection of several factors, primarily the difference between life in the wild versus in captivity and the seasonal availability of their food.

Wild vs. Captive Flamingos: A Tale of Two Diets

A wild flamingo’s diet is naturally packed with the carotenoids it needs. The specific types and concentrations of algae and crustaceans can vary by location and season, leading to different shades among wild populations. The American Flamingo of the Caribbean, for instance, is often much redder than the Greater Flamingo of Africa because its local diet of brine shrimp is richer in canthaxanthin.

In captivity, it’s impossible to perfectly replicate this natural diet. Zookeepers and conservationists have to create a special feed for their flamingos. In the early days of keeping flamingos in zoos, many birds lost their pink color and turned white after their first molt. Scientists soon figured out the dietary link. Today, captive flamingo diets are supplemented with synthetic carotenoids to ensure they maintain their health and color.

| Feature | Wild Flamingo Diet | Captive Flamingo Diet |

| Primary Source | Natural brine shrimp, algae, larvae | Specially formulated pellets |

| Carotenoid Type | Astaxanthin, Canthaxanthin (Natural) | Canthaxanthin, Beta-Carotene (Added Supplements) |

| Color Consistency | Varies by location and season | Generally consistent and managed |

| Benefit | Natural, indicates foraging success | Ensures health and color without natural habitat |

So, if you see a pale flamingo in a zoo, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s unhealthy. It could just be that its diet has a different balance of pigments than its wild cousins.

Seasonal Shades and Regional Hues

Even in the wild, a flamingo’s color is not static. The intensity can change throughout the year. During the breeding season, flamingos often display their most brilliant colors. This is no coincidence. A bright pink coat is a sign of a healthy, well-fed bird that is good at finding food. It acts as an “honest signal” to potential mates, advertising that the bird is strong and capable of raising chicks.

After the breeding season, or if food becomes scarce during a dry spell, their color may fade slightly. The energy and pigments required for mating and raising young can take a toll, leaving less for feather coloration. The pink will return in its full glory once the flamingo molts and has had time to feast on more carotenoid-rich meals.

More Than Just Good Looks: The Function of Flamingo Color

While the pink color is beautiful to us, for a flamingo, it serves a much deeper biological purpose. It’s a key element in their social structure, mating rituals, and overall survival. The color is a direct, external readout of an individual’s health and fitness, playing a crucial role in the continuation of the species.

A Sign of Health and Vigor

As mentioned, a brighter flamingo is a more desirable mate. This is a classic example of sexual selection. Females are more attracted to the males with the deepest pink or red feathers, as this color is a reliable indicator of:

- Good Foraging Skills: A bright bird knows where to find the best food.

- Strong Immune System: The metabolic process to convert carotenoids is complex. A healthy bird can do it more efficiently.

- Parental Fitness: A well-fed bird will be a better provider for its chicks.

In a way, the color acts as a resume for potential partners, showcasing their qualifications without a single word.

The Color Fades: What Happens to Pale Flamingos?

A flamingo that is pale or white is sending a different signal. It could be young, sick, or malnourished. Flamingo chicks are born with soft, downy grey or white feathers. They don’t start to develop their pink hue until they are one or two years old, once they have weaned from their parents’ crop milk and started eating a pigment-rich diet on their own.

An adult flamingo that loses its color is often a sign of trouble. If it can’t find enough food or is suffering from an illness, its body will divert resources away from pigmentation to more essential functions. This can make it less attractive to mates and potentially a target for predators who sense weakness. The link between diet, health, and color is a constant, powerful force in a flamingo’s life.

Frequently Asked Questions

What would happen if a flamingo stopped eating carotenoids?

If a flamingo’s diet no longer contained carotenoids, its new feathers would grow in pale pink or even white after its next molt. The existing pink feathers would remain until they were shed, so the change would be gradual.

Are baby flamingos pink when they are born?

No, they are not. Flamingo chicks hatch with fluffy grey or white feathers. They begin to develop their pink coloration over the first one to two years of their life as their diet shifts to include carotenoid-rich foods like algae and brine shrimp.

Do flamingos produce the pink pigment themselves?

No, flamingos cannot synthesize their own pink pigments. The color is derived entirely from the carotenoids found in the food they eat. Their bodies are simply very efficient at processing these external pigments and depositing them into their feathers.

Can a person turn pink from eating what flamingos eat?

While eating an extreme amount of carotenoid-rich foods like carrots can cause a person’s skin to take on a yellowish-orange tint (a harmless condition called carotenemia), humans lack the specific liver enzymes that flamingos have. We cannot metabolize carotenoids in a way that would turn our skin or hair bright pink.

Conclusion

The flamingo is a spectacular walking testament to the power of diet. Its iconic pink color is not a genetic trait but a direct and beautiful consequence of its place in the ecosystem. From the microscopic algae that produce the initial pigment to the complex metabolic pathways that paint each feather, the entire process is a perfect example of nature’s ingenuity. Their color is more than just decoration; it is a vital sign of health, a tool for courtship, and a direct reflection of the world they inhabit. So, the next time you see a flamingo, you’ll know that its breathtaking beauty is really just a colorful, feathered food diary.